The Good Brother

Volume Four.

Pearlcoombe

August 24thMy Dear Lizzy,

I know you will wonder at my writing to you so soon after your return to Longbourn, but the news- or rather the confirmation -came so suddenly as to preclude otherwise.

Be assured I am well, as well as any woman can expect to be so upon learning of a little addition to mine and dear Charles' happy union. We expect to have Pearlcoombe noisy with childish delights in the new year.

We left Pemberley as you known but a day after yourself, and since then have had no news from the place, other than Miss Darcy is presently enroute to Matlock.

Charles believes his friend has much work to do on the estate, though he knows not what the work could possibly be, for he remembers hearing his friend involved upon it while in London.

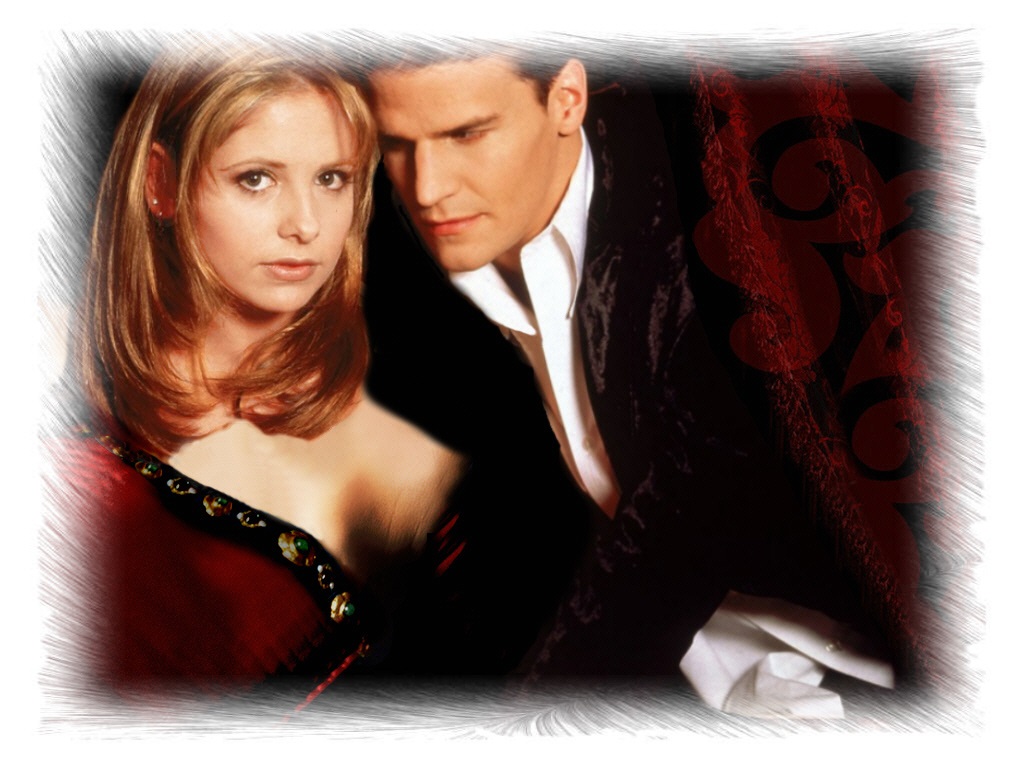

Nevertheless it is not the motive of this letter to talk of him, but rather of your feelings towards him. Lizzy, I am not so involved in my own happiness to notice that you and he talked frequently during our stay in Derbyshire, and his often distraction while out of your company. Surely you yourself noticed his attentiveness to you?

I cannot recollect a moment during all the time we were all together there when he was not in your company. One occasion in particular comes to mind; he watched you throughout your performance at the pianoforte, and with such a look upon his face as to erase all doubt of what he felt for you.

You will protest to this no doubt, but I saw your concern for him. Charles has told me that he confided to you his concerns over the state of his friend's health, but I would not know my sister as well as I claim to if I did not witness something else, some other feeling from you than just concern and duty you felt regarding Anne.

If such a suspicion on my part is false, then I beg you to forgive me and we shall never speak of it again. But if it is true, I beg you not to worry yourself over the rightness of feeling it. He clearly feels the same for you.

If your hesitation is a result of Anne, remember what she told you concerning their marriage. Such a future union would cause much happiness to your families, friends and especially yourselves. Delay is only needed for Society's sake, and since when did you much care for what others thought of you?

I hope, dear sister, that you will consider all of the above seriously, and send me a reply only when you have thought fully over the whole.

Yours etc,

Jane Bingley

It would cause considerable surprise to all concerned if Elizabeth, after reading such a letter, did not react with astonishment and consternation.

She had not been a week back at Longbourn when she received it, and the reaction that it caused was such as one would expect from one so unsuspecting that another had seen the feelings which had arisen in that county and the strange idea that he felt the same.

For a long

time did she sit in the garden grove where she had first retreated to read the

letter, pondering over the revelations.

When she had first returned to the bosom of her family, Elizabeth had been so caught up in talking with her father, her sisters and listening to her mother, that she had scarcely time to reflect over what had happened in Derbyshire, let alone any thought of him. Only now did she realise that her avoidance had be unconsciously deliberate.

For Jane

had stated the truth. She did still feel for Mr Darcy the feelings that had been

awoken in Derbyshire. The degree and intensity of them had not lessened, indeed

quite the opposite, increasing so gradually and so silently in her mind that,

almost immediately after reading Jane's letter, she could not protest them without

lying to everyone that knew her, including herself.

But the idea of he actually returning those feelings was the thing which made her so astonished to remain where she was until her father came to tell her that it was time for supper. Joy at the idea slowly faded into uncertainty as she recollected the events of her vacation, striving to remember if there was any occasion when he had paid her more attention other than that due of a good host.

Jane's recognition of the

recital evening could not be confirmed by herself, for she had been wholly concentrated

on performing the piece to the best of her ability to notice nothing else. No

other impression came to her mind that could confirm her sister's suspicions.

Yet, the thought did occur that she might be so determined to think that

he could not feel for her what she felt for him so far that her own view of the

stay was clouded beyond true and impartial recognition.

However, after just such a concept had occurred to her, Mr Bennet came upon her, and Elizabeth was obliged to forget the matter entirely for the rest of the evening. Indeed, during the days immediately after her return, she was unable to give the matter any attention, for other persons feelings required to be looked after.

There was her father to consider, whose penchant for her did not frequently conquer his abhorrence for the pen of correspondency, and as such had much to talk with her about which she had missed during her absence.

The occurrence of their daily evenings

together in his study only resumed after her mother and her sisters had exhausted

their need to tell her of all that had happened while she was away, and to ask

whether she had acquired any new beaux.

Then, just as the days returned to normalcy in the Bennet household, their evenings were taken up with the addition of the Phillips and then the Lucases for dinners and social engagements, along with the rest of the four and twenty families that Mrs Bennet claimed amongst her closest friends.

Elizabeth was obliged to be all that sociable and dutiful

of a daughter, as well as fending off her mother's entreaties on any new- and

sometimes old -eligible personages, and make sure Kitty and Lydia resorted not

to their usual wilderness.

Thus, it would be many days and many events would have occurred before Elizabeth ever had time to think upon all that Jane had written to her.

Part

XXIX.

With the arrival of Michaelmas signalling

the full circle of the year which first drew all in to the events in Hertfordshire

and its surrounding counties, the house that begun it all had been closed up for

four months.

Since the quitting of Mr Charles Bingley, the owners of Netherfield had received no requests to lease the place again. The servants had been transferred or dismissed, its windows and doors shut up, and its game allowed freedom of its skies and grounds without the risk of being shot once more.

Speculation as to who might take up the place had long been exhausted by this time. Many- those who regarded Mrs Bennet as the least interfering and matchmaking of all mothers, indeed, compared to some in Meryton,- Mrs Long in particular -she was the mildest of all -had expected the Bingleys to remain at the place indefinitely and had been a mixture of astonishment and insulted when they quit the place in May.

The latter emotion soon dissipated in the wake of speculation that another eligible gentleman might take up the place, which accordingly faded into disappointment as the months passed and no such circumstance occurred.

Ergo, by the time the Netherfield estate began to display signs of life once more, the personages of Meryton, Longbourn, Lucas Lodge, the great house at Stoke and Hay Park, had forgotten about the place; though if you were to recall such a opinion aloud to them, they would deny such a truth entirely.

Its closure was reversed

slowly; with the gradual arrival of a household staff, followed by the slow renewal

of shooting on the estate, but so sporadic was the latter that it was hardly noticed.

Only when Mrs Long happened, quite by chance,- at least that is her excuse -to

pass the house, and look up to see the windows no longer shut up, that the news

of Netherfield being let once more made itself known to the immediate neighbourhood.

Conjectures as to the identity of the new tenants duly followed,

beginning with the brief expropriation of servants in order to try and gleam the

names of who they served. However, unlike the last time, the servants proved difficult

to persuade and refused to yield any information concerning whom they obeyed.

Eventually, the tenant himself, being a man of quick parts,

caprice and wit, let the neighbourhood know who he was, by posting a notice in

the local newspaper. The name at first did not bring full understanding to all,

and most complained that it had been done so very ill; just Lord Edward Fitzwilliam

and family, without a syllable said of where he came from or what his family entailed.

Only one guessed the full at once. Elizabeth could not help but gasp at the news, knowing of one Fitzwilliam family. Confirmation came a day after the announcement, with a letter from Jane to herself, relating the news that the Matlocks had travelled to Pemberley and then set off for Netherfield, bring their nephew and niece in tow.

It was at this moment that Elizabeth returned to considering her feelings and the possibility that the man in question might reciprocate them. Indeed she could not foresee any other reason that would bring him to Hertfordshire.

She went to bed that night with the matter still heavily upon her mind, and perhaps it was due to this that when she woke the next morning, a memory she was unaware of ever having existence was the first thing to possess her mind. Opening her eyes she was disappointed to find that it had only been a recollection, so vivid was the sensation of his breath, his touch and his words.

You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you that was what he had said, just before she had lost consciousness, that night when he had happened upon her at Hunsford Parsonage. She remembered now, just as she remembered him caressing her cheek, and smoothing away a curl of hair in accompaniment.

Despite the suddenness of this revelation, Elizabeth could not doubt its truth. Arising from her bed, she went to her bureau and opened a drawer, from where she took the letter that her tumult of emotions could no longer bar her from reading.

Hunsford

April 11thMy dear Elizabeth,

I write this with the knowledge that I have not long left upon this world, and with realisation that unless such a thing is written, the future I hope for you and my cousin will never occur.

Doubtless such news of my hopes will cause you much surprise, so without further ado, I will relate to you the whole.

I had not long been in Hertfordshire before I saw that William was attracted to you. Knowing my cousin as well as I did told me at once how events would proceed; he has never looked at any other before you and is unlikely to look at any other after you.

By the time of the Netherfield ball he was in love with you, of that much I am certain. The only thing that stood in his way, was me.

Depending on when you read this, and the progression of events, I know not how you will treat this certainty of mine. Astonishment will most likely be one feeling that will possess you, along with disbelief of what I write.

I know not how to assure you of the truth. William has not confided in me or anyone else what he feels, yet I know it. I witnessed all his unguarded looks at you, saw and heard all his praise of you that he felt he could express before he realised what he felt and thought there was a need to be circumspect.

I have never seen him in love before, but I know him to be so and with you. How you feel for him is less certain at present to me.

Since what he told you of Wickham and our marriage I know that you see him for the good and generous man that he is, but whether you have yet to begin to regard him as someone with whom you could spend the rest of your life with remains unknown to me.

You have been such a good friend as to make me feel disgusted with myself as to what I am about to ask of you when I know my eternal farewell is imminent, but I cannot let the words remain unsaid.

If you have any degree, no matter how small, of the feelings that he feels for you, please tell him. I know him too well to know that if you do not, his guilt may drive him to the point of death over his for you.

I do not wish to make you feel guilty if you cannot express the feelings; nor do I wish you to feel obligated into carrying out such a notion anyway, out of some misguided duty towards me.

I only wish to let you know that if you do not tell him of what you feel, he will never have the courage to tell you. His sense of duty has so long been ingrained upon his character that the idea of you returning his feelings will probably never occur to him, unless you let some of your own show.

I know that you think him to be a good man, a good cousin, a good brother, so the possibility that this will grow into more and this hope of mine concerning your feelings is not entirely in vain.

I wish so much for him to have the happiness in life that he has deserved for so long. The happiness that I could not provide him, for we were never in love and never hoped to be so either.

I wish I had the time or the strength to persuade you to think and feel the way I wish you think and feel about him. But I know I do not. Therefore I can only hope that my wish is father to your thought.

So, dear friend, I bid you adieu, and hope that you do not throw this letter out in disgust, but instead consider all that I have told you and the extent of your own feelings towards him.

Anne.

The knowledge that her recently departed friend had not only known all along, but had also given her blessing to the matter, comforted Elizabeth almost immediately.

Her estimation of Anne was increased by this news; that she could be so concerned

with the happiness of her friend and husband of convenience while she was suffering

her fatal disease made her all the more worthy a friend.

Only one thing was left to distress her. That was that she had yet to hear of his feelings for her from the man himself. Until then, she could do nothing but hope.

1. "Thy wish was father, Harry, to that thought." Henry IV, Part 2 (1597) act 4, sc. 5. William Shakespeare.

The motive of the Edward Fitzwilliam, Earl of Matlock, in letting Netherfield, was twofold. Firstly, it was in the hope that the move would bring his nephew back into the land of the living; for it had been the solution that offered itself after they had been made aware by Georgiana of his state of health.

Secondly, it was also in the hope that it might persuade his own sons to quit the bachelor state. After all, if Hertfordshire had the ability to make one of the bachelor quartet- as he had referred to his sons, Darcy and Bingley in private -quit the state for matrimony and another fall in love, it must possess wonders previously unequal to those anywhere else.

Goodness knows he had certainly tried everywhere else. Where London had failed, he hoped Bath would succeed, and when it became certain that the latter was not having much success either, any other place and or county in whatever order after that. His last resort had been before this county, the residence of his sister, but, knowing his sister as he did, he remained convinced that any visit there was more likely to do the opposite, and scare them off matrimony all together.

At present, all of this remained unknown to the general populous at large. Indeed, as these were the private thoughts of the Earl, how could it otherwise? Yet, unknown to all, those thoughts and hopes were about to be revealed to one man of the neighbourhood, a surprise to all concerned, including the gentleman himself.

Mr Bennet- for it was to be he -came to a halt outside the front entrance to Netherfield and wondered for the tenth time that morning why it was he was doing this. Why he was bowing to his wife's wishes? Surely, there were other places of retreat where he could disappear to until it was safe to emerge?

Yes, but Mr Bennet's thoughts were wearied by his wife's constant discussion, her attempts to persuade him to call, and thus had dealt their revenge by persuading him that he had best oblige Mrs Bennet's wishes and proceed forthwith.

His thoughts however were also due to get their comeuppance. For they had failed to remember one thing. The unpredictability of fate. It had the ability to completely against one's wishes and plans without warning, reason, or motive, save perhaps just because it liked to do so.

In any case, whether it was due to a severe case of scarlet fever, different schooling, or just luck of the draw, fate was to intercede yet again on behalf our hero and heroine, by granting a circumstance and connection previously both unknown and unforeseen by all.

But to resume. Mr Bennet was shown into the Drawing Room of Netherfield, and introduced to the Earl before any idea of there bring some unforeseen past connection was made aware to him. Thus he was completely surprised when rising from his bow to be greeted by a familiar voice calling him to remember a friendship of old.

Edward Fitzwilliam, by curious luck of birth and education, had started off life as the fourth unnecessary son of the late Earl, who having already three others before him, saw no need to pay any special consideration to his upbringing. He was sent to Eton and then to Cambridge more out of familial tradition than actual design.

But, after having graduating from the latter, Edward soon found himself swept up the ranks from fourth son to first and heir. Barely a year passed to allow him time to adjust to this extraordinary state of affairs before the Earl had departed his mortal body as well, leaving Edward little time to learn how to run the massive estate left him.

It is not the intention of this tale to describe in detail how he rose to the occasion and beyond, in fact the entire sequence of events is not at all important to us. All that needs to be said that it was while Edward was at Cambridge that he met and formed a friendship with Mr Andrew Bennet Esq. a friendship that had remained until graduation, when events prevented either of them from keeping in touch.

Both possessed the mixture of quick parts and caprice, the ability to laugh at the absurd and express profound wit and intelligence. In Edward's case though, he had a whole family to share the amusement with, whereas Andrew had only two daughters.

Their previous connection once remembered, thus laid the way for both to sit down and fall into conversation, relating to each all that had occurred between their college days and their present reunion. The quirk of inheritance soon drifted into talk of their offspring and relations, as Edward related his reasons for letting Netherfield.

Mr Bennet, naturally surprised at the state of affairs between his daughter Elizabeth and Edward's nephew, had no unfavourable opinion of the latter to give the possible future match anything but his blessing. Plans, outcomes and solutions were set, waiting to be put into action.

Edward then turned to the matter of his sons. "Richard I know," he remarked to Mr Bennet, "is married to the army, but Alexis has no excuse. If he can only find someone as sensible and as practical as he then he ought to be blessed, but the woman has yet to be seen to exist.

"Lord knows I have tried to search for her. So thoroughly in fact that this county must succeed where others have failed." Edward sighed and took another sip of his port. "After that, there only remains my daughter Eleanor, and do not get me started on her."

Mr Bennet merely chuckled in reply. "If she's anything like my two youngest then I pity you, Fitz."

"Well, its partly my own fault. She's had too much of Richard's influence from an impressionable age, thus she far more content fencing with him than making bonnets." He set down his drink. "However she is also only eleven, so I do not need to worry seriously as yet."

Their conversation returned to other matters, and when Mr Bennet reluctantly rose for Longbourn, it was with a happy recollection of the meeting, and a healthier respect for fate than he had ever had before.

From an upper window, Fitzwilliam Darcy watched the father of the object of his affections until he had disappeared around a corner out of sight. He knew his Uncle too well to mistake what their meeting had been about. Whether he feared or welcomed the intervention however, remained as yet uncertain and unclear to him.

The day that his Uncle and family had arrived at Pemberley was still clear in his mind. Having been out in the wilds of his lands, no news of their arrival was given to him until he returned for dinner, and encountered them in the Music Room, where Mrs Reynolds had installed them and given them their bedrooms until her wayward master saw fit to return to play host.

Images of their shock and disapproval at his state returned frequently without warning to his inner eyes, making him even more ashamed at himself for letting things slip so low. Having been raised on good principles he had always tried to live up to and beyond their expectations. This was the first time he had failed them, and the failure did not sit well with him at all.

However, he was at a loss for a solution. Restoring his health to what it had once been was immaterial if he could not restore his emotions or his heart to the same standard. He did not think he could spend the rest of his life just surviving on that alone.

But the state of both entities were dependent on factors out of his control. While he no longer doubted that he had done the right thing in marrying Anne for her sake and Georgiana's, not for his own, he doubted that it had done any good to his own mind and body.

Yet it was not in the nature of a good brother to do other than devote himself solely to the well-being of his sister, no matter at the expense to himself. It had been an arrogant presumption on his part to presume that a marriage of convenience to a dying cousin would not have any adverse affect upon him.

The fact that neither he nor Anne had known that she was dying until after their marriage had nothing to do with the matter. He had made the presumption and now he was suffering the effects of it.

To him, it was simply a matter of taking one day at a time.

How little did he realise that events would spiral out of his control, securing an outcome that would prove beyond all his expectations.

Having enjoyed the first visit, Mr Bennet could be reasonably assured of enjoying the second. And it was with this and more in mind that he returned to Netherfield the next morning.

He did not return alone. By previous design between him and the Earl, he had managed to persuade Elizabeth to accompany him upon a walk, which, by pure chance of course, would take them by Netherfield, outside which the Earl, would 'just happen' to be walking.

Naturally introductions would ensue. The Earl would then cry, "Oh, Miss Bennet! Do come inside, you and your father. My niece Georgiana has been dying to see you ever since we arrived here."

Elizabeth was thus caught. Realising now the truth of the expression upon her father's face, she chose not to react how he expected, and followed the Earl into the Entrance Hall of Netherfield.

Almost immediately were they greeted by the flying appearance of a tearful Miss Darcy, as she flew to Elizabeth's arms.

Miss Bennet was all astonishment. "Dear Georgiana, what on earth is the matter?"

Georgiana seized upon her with relief. "Oh, Lizzy, I am so happy to see you! Come, walk with me, we must talk."

With that she led her off to the other side of the house, and out into the formal gardens. The Earl and Mr Bennet observed their departure, smiled at each other in appreciation at the success of their plan's first phase, and retired to the Library.

Meanwhile Miss Darcy had secured her arm in Miss Bennet's, and proceeded at once to confide in her.

"Oh, Lizzy," she began, "I am so grateful to see you at last. Things have been so dreadfully amiss."

"My dear Georgie," Elizabeth could not help to entreat, "what is wrong?"

"It is William, my brother," was the response.

And so began the tale. Elizabeth found herself to be grieved indeed by the conclusion of it. Grieved, shocked. She could not doubt its certainty, for Georgie was too dismayed for it to be anything other than truth.

"And has anything been done, has anything been attempted to aid his recovery?"

"Nothing at all, until now. There was nothing that could be done, unless we found a means of getting him away from Pemberley, where he can avoid us. We hoped this move would deprive him of the excuses which he has used to escape detection."

"Then you must not lose hope. You have only been here a few days. It is too soon to notice an alteration."

"Yes, you are right. But still I worry. He is the closest person I have in the world, and I would not be able to bear his loss." Georgiana paused to gather breath, then tentatively asked, "Lizzy, would you..... that is... I would be most grateful for your assistance."

"What assistance could I possibly provide?"

"Support. You help me achieve so much at Pemberley, when he was in such a state before your arrival. Please, Lizzy, it would give me so much ease."

"Very well, I will. I cannot bear to see you upset."

"Thank you, Lizzy."

Elizabeth took a longer, more solitary route back to Longbourn, an hour or so later. Her mind was overwhelmed by all that she had just heard and seen, turning emotions that, only a day ago, she had been sure of, into a conflicted mass of self doubts.

So surprised had she been at her father's design for their walk, an emotion which had then increased with every passing minute spent at that estate, bringing along with it shock and grief, both at Georgiana's words, and the sight of Mr Darcy himself.

Yes, she had seen him. After making her promise to his sister's earnest entreaty for her assistance, Elizabeth followed her back into the house to rejoin her father and Lord Matlock, only to encounter the gentleman that had been the object of their conversation enroute.

She could not restrain a gasp at his appearance. She had seen him neglect his health before, but it had been as bad as this. If they had been alone, her impulsive decision to wrap her arms around him would most likely have been obeyed, but they were not alone, so all she could do was stand and stare, as she took the full state of him in.

He had seemed as shocked to see her as she was to see him. Standing for a minute in silence, he had then enquired in tones of agitation after herself and her family. His frequent repetition of some inquiries showed plainly the distraction of his thoughts.

When she had asked after himself, purely to see what he would do in response; he seemed to hesitate, look longingly into her eyes, before answering, "I believe I have newly gained some improvement towards my previous state."

Never before had his implications been more clearer. Elizabeth had blushed, then looked away, only to see Georgiana smiling in appreciation.

Mr Darcy then took his leave, adding in farewell, that he was truly glad to see her again, surprising her by taking her hand in his almost frail own, and raising it to his lips.

It had only the briefest of kisses, yet it had been enough to make his sister gasp, and her to blush once more. She blushed even now as she thought of it, and as her other hand stroke the skin which he had touched, as if she could spread its imprint on herself.

This was the first time which she had encountered him with certain feelings and sure emotions of what she felt for him. At Pemberley she had believed herself to be under the spell of the estate, but now, her feelings were more clear, and had remained the same too long for her to doubt them any more.

Anne's letter had helped remedy a lot of her previous conflict. She wondered now if he had received one, and if so, whether he had read it yet. Would it contain the same thoughts that Anne had conveyed to her? Elizabeth could not believe that it would not be unable to avoid some mention of them, lest she had completely mistaken her late friend's meaning.

Had she mistaken it? No, the words were too precise, the meaning too distinct to interpreted in any other way. Would he have received one? Or had Anne time and strength to talk to him about the matter? Elizabeth thought back to when she had been at Rosings, trying to remember if there had any indication which would support the last possibility.

You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you. When had he said that? The night before she had learnt that Anne was gravely ill. Surely if his feelings had been clear enough to him then, it were a sign that Anne had talked to him?

Or had they just been struggling within him so long, that he had been unable to do anything else but tell her? Had he meant for her to hear them, or had he meant for them to remain unheard?

Elizabeth decided that it was the latter. This, coupled with certain phrases in Anne's letter to herself, showed that she had not spoken to him before then, only observed and drawn her own conclusions.

Did he still feel the same? Did she? At this moment, Elizabeth could not tell if her feelings were more to with pity at his state since the passing of Anne. Why had she been so certain of what she felt for him before? Was it because they had been apart, and her vanity had been flattered by his spoken phrase?

That is, if he had really spoken it, and she had not dreamt it, during the unconscious sleep brought on by the headache she had felt that night. Oh, she hated this self doubt. He needed to be well again, she needed to see him restored to his previous self, then would she be able to sort out her feelings for him.

Darcy did not know how he had managed to walk away from her. All he could remember was reaching the south entrance, walking to the stables, and saddling his horse, before riding as fast as he could into the wilds of the Netherfield estate.

He had not expected to see her so soon. Nor had he expected to derive any pleasure from it. He had thought himself too ill, too conflicted with emotion for that. Yet pleasure he had felt, along with joy, and in so much abundance that he could barely refrain from smiling at her.

She had seemed just as surprised. Most vivid in his mind were her blush in reaction to his last words, and then another at his kiss upon her hand. The decision to make that act had been completely impulsive on his part.

He had wanted to do so much more than kiss her hand. He had wanted to wrap his arms around her and kiss her lips. He had wanted to kneel at her feet, and ask her to be his wife.

Would he had followed through with these if they had been alone? Upon reflection Darcy decided not. He was still too unsure of himself, still too unsure of her feelings, to possess the courage required for such an endeavour.

Sometimes he wondered if he could ever be certain enough to do what was so desired for his future happiness. Was he being too selfish, at the thought of it? Did she deserve a man so dependent on her feelings for him for his state of being?

No, she deserved better than he. But Darcy had tried to tell himself that too many times. Always after the thought had crossed his mind, would he suddenly think of a certain look, or word from her, and that would be enough to convince him to abandon that noble intention.

Could he really be so sure that she cared for him? Or was he only seeing her pity at his neglect of himself, a part of the friendship she had felt for Anne, transferring to him, out of some promise she had made to her before she died.

Darcy halted his horse, and dismounted, allowing the stallion to catch his breath, and feed upon the grass before they returned to the house. Careful not to mark his breeches or jacket, he sat down beside the steed, clasping his hands around his knees, as he stared at the countryside beyond.

His thoughts however were still focused upon Elizabeth. What had she, he wondered, thought of Anne's letter? For that matter, what had Anne written to her? Darcy did not know, for he had reluctantly left Anne alone that day, returning only when she had finished writing them.

Never once had he thought of breaking her privacy, only following her request, and handing each one to the persons they were addressed to.

Only two things he had yet to do which he had promised her. Firstly, was Lady Catherine's letter. At the time of Anne's death he and his Aunt had still been on anything but speaking terms, rendering it impossible to deliver it to her. The letter still remained in his correspondence ledgers, in a bureau in the library of Netherfield.

Another letter, equally unopened, lay with it. It was Anne's letter to him. He still did not have the courage to break its seal and read the words contain therein. For the first time he wondered if she had ever guessed what he felt for Elizabeth. He wondered that, if she had, if the letter contained anything concerning it, maybe even going so far as to give her blessing to it.

Did he need her blessing? True, theirs had been a marriage of convenience, but they had always been close friends, despite the wishes of her mother, and putting aside that first factor, he would still like to have it all the same.

Was he being too presumptuous however? He had been so careful to conceal the feelings for Elizabeth; had they truly remained undetected to all? Before Anne had fallen gravely ill, Darcy had been certain that he had managed to hide it from everyone, but since her passing, the doubts had grown until he was unable to ignore them. Now he was even more conflicted.

His horse neighed, which, together with the ringing of the Church bells, announcing the hour, brought him out of his thoughts. Back to the reality at hand. It was late, and he should be returning, lest they send out another searching party for him. Slowly he rose and mounted his steed, a decision now clear in his mind. He would read Anne's letter. It was time.

One might think that after the arrival of such a decision, the gentleman who had made it would stop at nothing, or forgo not overcoming everything and anything which might lay in the path before it, to carry out that decision immediately.

Indeed, Fitzwilliam Darcy tried. He went straight to the bureau that held the all important letter, placed the key inside its lock that posed as a barrier to opening the drawer, and turned. The click of the sliding metal barrier sounded impossibly loud to him in the silence of the room. However, barely had he turned the key, before another realisation came to his presently much tortured and taxed mind.

That he should learn to lock doors to rooms that he wishes to be undisturbed from. This was not Pemberley; he was no longer in possession of the privilege that comes in having one's own house and the right to bar anyone access from any room that he chose to inhabit for any length of time.

No, this was Netherfield; presently let by his Uncle, a relative that usually he regarded as one of the most astute gentleman ever to have existed upon this earth. The fact that he only usually regarded him as such was the point in question. For it was the very same relative which now disturbed him from his present mission.

As was custom in the way of intruders who have no possible way of foreseeing what the person that they have just intruded upon was about to do, the Earl noticed not the not terribly well concealed Medusa glare that his nephew was presently sending him. Or if he did, he chose to refrain from commenting about it. "Ah, there you are, Darce. I have the greatest need of you. Have you a moment or two to be at my leisure?"

Darcy was sure that the Earl knew perfectly well- at least he ought, by the looks he had been sending, else he was not as sensible and as intelligent as he regarded him to be -that his nephew right now, did not, have a a moment or two- for inevitably it would take longer than what he judged to be a moment or two -to spare his uncle.

Indeed he happened to perfectly correct in supposing this, for the Earl knew that his nephew did not, but just enjoyed seeing the expression of exasperation that was currently on Darcy's face.

Putting this aside however, Darcy also knew that his uncle was

also his host, and that he had a lot to be grateful for to him at present, namely

dragging him- no, dear readers, you have not misheard, he was dragged, indeed

when he is being stubborn, how is he to be swayed otherwise? -to Hertfordshire

so that he might accomplish what he had done so far; see the woman who held eternal

possession of his heart.

Therefore Darcy replied that

he had all the time in the world to serve his Uncle. Those were not his exact

words you understand, for he did not want to seem sarcastic, or anxious for favour,

but they still convey the general meaning.

But to resume.

The Earl, having received the reply that he wished for, continued. "Excellent.

Do you, by any chance, happen to know who Sir William Lucas is?"

Darcy

almost groaned. He half knew what was coming next. "Yes," he said with

the tone of a man who knows his immediate future fate and has no means of escape.

"Why?"

"Because the gentleman is at present

waiting to be admitted into the present of my family to pay his respects, and

until now, I had never heard of him in my life before. I would be grateful therefore

if you could come with me and be able to carry the conversation."

The

Earl could not have asked at present a more difficult task. Darcy turned the key

in the drawer back from its previous position, put the key back in his jacket

pocket, and with one last look at the bureau, left the room with his uncle.

It would do well on my part as the humble author to mention at this point that this event did not take place on the same day as when we last visited this county. Indeed the late hour that the church bells signalled had been dinner, precluding Darcy from attending to the letter from Anne until the hour which he could, safely, without having to explain himself, retire.

However

that hour was also late, and as a result it prevented him from being in any fit

state to think calmly and rationally about what the letter said, let alone read

it to begin with.

Thus it was now the late morning after, Darcy having been prevented from getting to the letter and securing the time alone needed to read and reflect upon it, until this first attempt. And this first attempt would turn out to be his only at the end of the day. For Sir William Lucas, having discovered that the tenants of Netherfield had a prior acquaintance as a relative, and this relative was with them, and in the mood to talk- or rather listen -spent most of the day in their company.

Being a man with a unmarried children, particularly two girls who were both of eligible age, and a wife who had not ceased her pestering of him until he had relented to obey her wishes, he was determined to waste no time in finding out if there were any eligible gentlemen staying with the Earl, and what connection they had to him.

Finding out that they were heir, spare and nephew was more than he had dared hoped for. The fact that the spare was a full Colonel and the nephew was one of the most illustrious personages in the land, could not be anything else but an added bonus. True the latter had previously been married and had shown no interest in either Charlotte or Maria, but that did not mean that he did not stand as equal possibility as either of the other two as possible future son in laws.

Therefore, Sir William almost transformed

into a certain cleric of our acquaintance, singing- not literately I assure you

-the praises of his children until it was hinted more forcefully than the last,

that he had taken up enough of the Earl's time. However, he did not leave without

securing an acceptance to attend a little gathering at Lucas Lodge in two days

time.

His duty now over, Darcy began to make preparations to get the solitude in the library he had previously failed to achieve. Circumstances however, were to prevent him once again. For Sir William had stayed beyond and past when the family usually ate, making the hour now time for tea, which precluded anyone from going off on their own.

So Darcy sat back down and exerted himself

into answering the request of his uncle to acquaint him with what he knew about

the neighbourhood.

There was at least one reward from this chat. Darcy discovered his uncle's previous friendship and its present renewal to Mr Bennet. Such a connection could not afford to be overlooked, and Darcy knew well the advantage that it might give him.

Due to his previous time in Meryton,

he knew that Elizabeth was her father's favourite, and therefore, gaining his

approval would give him some aid into accomplishing his hopes and desires for

the future.

So when he did at last have an opportunity to make a dash for the library, Darcy did not feel that his imposed delay had been wasted. But by the time he did try again, he began to wonder if the entire world was preventing him from succeeding.

First his uncle and Sir William, now an express from his Steward. The latter, Darcy knew, was a very capable man, else he would never have employed him in the position he held in the first place. For him to send such a letter must mean a grave emergency, and he at once put aside the letter he dearly wished to read.

Naturally,

an evening at Lucas Lodge with the assured attendance of the new tenants of Netherfield,

was not something that Mrs Bennet wished to avoid. Therefore, once she had heard

about it from Lady Lucas, she wasted no time in taxing her husband- he called

it taxing, she preferred to refer to it as persuasion -until he agreed that they

would go.

Mr Bennet, once he had heard the full details of the evening

in question, was perfectly willing to comply with such a usually irksome request.

However, he was not about to let Mrs Bennet know that. Such a lapse in character

type would ensure the methods that she used to be repeated when another, less

welcome diversion from his sanctum would be required by him, and thus he could

hardly afford to lose the advantage which his strong resistance usually gave

him.

Eventually, Mrs Bennet obtained her wishes. She then announced

the evening to her remaining daughters. Lydia and Kitty naturally looked upon

the event with great enthusiasm. A man in regimentals was not a thing to be missed.

Indeed, a man not only in regimentals, but the rank of a Colonel and single, was

not a man to be missed by them upon any occasion. They spent the entire hours

until the event itself in a flurry of activity to prepare their gowns and themselves

ready for the Colonel to fall at their feet.

Elizabeth looked upon the evening with more fear than willingness. She had no Jane to confide in, only Charlotte, but despite their friendship, even she had not been as close to her as her sister was, by sheer fault of relation. Added to this, was the quite unavoidable fact that she might see Mr Darcy there.

She knew not yet how to face him, let alone talk to him. The memory and sensation of his lingering kiss upon her hand was still so vivid in her mind, that she doubted her strength to remain calm when she next set eyes upon him.

Not only was there he, but there was also Colonel Fitzwilliam, with whom that, although she did not care for him at all like she cared for his cousin, there was still a prior acquaintance, and one that had not been in the best of times, indeed, quite the reverse.

There was also the Colonel's father, whom she had discovered, after the visit to Netherfield, her father knew very well. And knowing her father as well as she did, she knew that his friends were holders of the same characteristics as himself.

Therefore she knew that her

every action towards Mr Darcy would be observed and interpreted; for, as she had

been informed by Georgiana, every one at Netherfield knew of Mr Darcy's condition,

and possibly his history with her, which meant that her father knew now as well.

Yet, despite all this, she did not wish to remain at Longbourn that evening. The fact that she could not any way mattered not; if she had the opportunity to decline, she would not. A part of her that she was unable to surrender to all her fears, wanted to go, wanted to see Mr Darcy again, wanted to see if he still cared for her the way she supposed he had, the way she cared for him. She wanted to see if there was an chance to accomplish her future happiness.

Unhappily for both our hero and heroine, the evening did nothing

to accomplish their expectations. For although both of them had planned to attend,

one of them could not.

Mr Darcy was that unfortunate person. He had desperately wanted to attend. Despite the need to read Anne's letter, the need to see her, to be simply around her presence, even if no occasion in the evening granted them time to talk, was greater than anything imaginable.

But he could

not. The express from his steward prevented him doing anything but shutting himself

in a room away from the letter- so it did not prove to be a distraction -and working

out the problem that he had been presented with.

In the end it was not as grave a problem as he had feared. Nonetheless, it did require many hours in the sorting out of a solution for it.

By the time of the day after the evening

at Lucas Lodge, Elizabeth knew the two words she could utter that would make her

dear friend Charlotte, blush. She had been astonished that only an evening had

managed to accomplish this much from her practical friend, but indeed it had.

"And how was your time with the Viscount Fitzwilliam, Charlotte?"

Miss Lucas could not prepare herself in time. She blushed at the recollection of it, of him and of his voice and manners, before realising that she needed to deflect her friend. This was too fast, it must be too fast for her to feel so much so soon.

"We had a pleasant conversation, yes."

Elizabeth

smiled at her friend with teasing eyes. "A pleasant conversation? As I recall,

he seemed to be doing most of the talking,"

"Lizzy,..."

"Whilst you stared up at him entranced, and when you did speak, one

word was enough to have him suffer the same affliction."

Charlotte

glanced at her friend, and saw an expression she knew all too well. She could

no longer deny the truth, else be teased all morning. "I must confess to have

enjoyed his company very much. But Lizzy, it is too soon, is it not? One cannot

possibly feel so much after only one acquaintance."

"Especially

if one has been so practical, never a romantic before?" Elizabeth added to

her companion's comments. "Charlotte, stranger things have happened."

"I do not think that anything could be stranger to me than this,"

Miss Lucas replied honestly to her friend. "Nothing could have prepared me

to believe this would happen to me. I am not like you, Lizzy. I do not have time

in my favour."

"Charlotte, you are but seven and twenty!

I know of at least one woman who is older but still unattached," Elizabeth

replied. "And thankfully, she is not here to try sway people with her orange

charms."

Charlotte laughed. "Lizzy, that is unkind."

Elizabeth smiled. "My dear friend, if you intend to utter Jane's most

serious rebuke, please do not with a laugh, for I shall know that you agree with

me!"

At this they both chuckled, before Charlotte sighed and came

to halt upon the path where they were walking, her face serious once more. "In

all seriousness, Elizabeth, can I really hope? Or is it too soon?"

Elizabeth thought over her recollection of the evening, remembering how the older brother of Colonel Fitzwilliam had spent most of his time in the company of her friend, and the looks he had constantly been in possession over when staring at Miss Lucas. "I think, Charlotte, that you can hope, if naught else. You have a good beginning, which makes all the difference."

Hunsford

April 11Darcy,

What was it about your first name that made you not respond to it? What was it about myself and the rest of your relations, that made us never attempt to call you by it anyway? It was always Darce, Darcy or William.

I remember the only one time I referred to you as Fitzwilliam. You seemed to blink, uncertain. As if you were disappointed at the way it sounded. As if you had dreamt of it sounding another way, from the woman you were to marry.

I apologise for this non sequiteur opening. Alas, I could not think of any other way to begin this letter to you. I struggled to open it with the same theme that I have begun all the others I had to write with.

You should see the other five versions of this that just become the latest fuel for the fire. I must thank you once for your excellent tutelage in throwing. My aim has improved so much.

You will find this letter disjointed I fear. Already I have drifted from my original intent. To resume now. The debate upon your name.

I know I was not the woman you wanted for your wife. I know that circumstances out of your control dictated this course to you.

I am not disappointed by that. I never held any illusions that we would submit to my mother and fall in love.

You were too much like a brother to me, and I know you always regarded me as another sister.

Nor do I regret our marriage. I am glad to have had some freedom from Rosings, and to steady Georgiana on her course for confidence after that dreadful Ramsgate affair.

I still remember your face when you told me of it; that first visit to Rosings since its painful occurrence. You looked so distraught, so sad. So ashamed at what you believed to be your failure to keep her from harm.

I know how deeply you wished to make your father proud of you, and how you thought him now ashamed of you. Dear Darce, he could not be more proud.

There was nothing that you could have done to prevent Ramsgate, unless you possessed the ability to foresee its occurrence.

The moment that I saw all those feelings of yours, I vowed to make you forget them. To help you in way that I could.

I did not expect marriage to be your proposal. I knew it would be difficult for you to find another companion that you trusted for Georgiana, but I did not expect for you offer the bargain that we entered into.

On a purely selfish basis, I do not regret our marriage. You helped me so much. Gave me many things for which I am so grateful. Freedom from Rosings has done wonders, never doubt that.

But, as I became more certain of my fate, I knew the union would not do you as much good as it has done for me. I know your disposition far too well.

Blessed with the view that you had of your parent's blissful marriage, I knew that you wanted the same for yourself.

Too many tragedies have come to you in your life, Darce. I am only too glad that they have not conquered you.

I know not when you will read this. I can only hope that it is not too soon after my passing, for I know that what I am to write next will affect you greatly. You would not be ready for it until I have been gone for months.

It is simply this; I know whom you love. I knew it almost from the first time I met her that you two were destined for each other.

I also know that my friendship and my passing will prove a hindrance to you both, so let me say, Darce, that I approve wholeheartedly of Elizabeth Bennet.

Do not attempt ignorance. You could not hide from me, we have known each other too long for that.

I know you will feel guilt for possessing the feelings that you possess for her, even though our union was always of convenience, and I know this guilt will continue long after I am gone.

You will be stubborn and resistant to this I am sure. All I am asking is that you do not let it affect you for too long.

If this illness has taught me something, then it is that we frequently take too much for granted, especially when it comes to our passage on this world. It is not the quantity, but the moments, that should be treasured.

I know you believe that she does not feel the same. But the foundations are there. All that need be added is time together, and you being your excellent self. Then I know, you will find happiness in your second match.

I hope this gave you comfort.

Anne.

Darcy laid the letter aside, his fingers going to his eyes, brushing the tears that had formed during his reading away. As soon as the grief and gratitude had faded, he felt anger stirring within him; directed at himself. Anne would not be happy if she saw him now.

He needed to recover; to be himself again before

he dared to enter that second match. He had neglected himself for too long. He

must present himself at his best to the woman that he loved. Only then could he

hope for the happiness he wished to achieve.

It was time to act.

"Oh, Mr Bennet! Such wonderful news I

have!"

Mr Bennet, with the greatest reluctance, looked up from

his book, and inquired, "have you, my dear? Pray, what is this news?"

Mrs Bennet's response was to wave a opened letter in front of him. She

did it quite well, and, had it not been for the look of exasperation upon his

face, would have continued. "It is an invitation from the Countess of Matlock,

to have dinner at Netherfield this evening!"

"Has the Countess

properly met all of us yet?" Mr Bennet queried. "For, I'm sure she would

not be so enthusiastic to see us all again so soon."

"Oh,

Mr Bennet! You take delight in vexing me! You have no compassion on my poor nerves!"

Mr Bennet would have replied to this, had it not for the entrance of his

daughters, and Miss Charlotte Lucas. With a smile did he turn and welcome them

into the room, noticing with some relief that his favourite seemed a little happier

than when he had last set eyes on her. "Is this invitation for us alone,

wife?"

"What invitation?" Cried Lydia.

Mrs

Bennet set eagerly about telling her dear girls the joy that awaited them that

evening. Her happiness at such notice from so prominent a woman, was only slightly

marred, by Miss Lucas remarking, "oh, I am so glad you are to come as well."

"You have been invited then, Charlotte?"

"Yes,

myself, Maria and my mother and father."

Mr Bennet observed his

daughter carefully as she listened to her friend's response. Was he mistaken,

or had her expression changed to one of slight apprehension?

"Well,

my dears, this is a great honour! Lydia, Kitty, we must go into Meryton today,

and purchase some new lace." And Mrs Bennet swept them out of the room with

her.

Mr Bennet turned to his daughter. "And you, Lizzy? Are you

looking forward to this evening's delights?"

To his surprise, his daughter answered, "Yes, Papa, I believe I am."

The evening soon came. Elizabeth, seated before her mirror, was deep in her thoughts as she waited for Sarah to finish her hair. Her reply to her father had been uttered in complete truth, though she had no idea why she was looking forward to the evening.

It would be only the second time that they

had met since his return to the neighbourhood; by all rights she should be feeling

apprehensive of what awaited her. Yet she felt perfectly calm. In fact, she felt

perfectly eager to spend the evening at Netherfield.

Sarah quietly

excused herself then to attend to the other ladies of the house, leaving Elizabeth

to survey her appearance. She was wearing the same dress that she had worn at

Pemberley, having cast many of her newer dresses aside, convinced that they would

not suit. Based on this, her mind seemed to be a mess of perfect calmness and

absolute nervousness. She knew not what to make of it.

This calmness

continued as she arrived with her sisters outside Netherfield. The Earl was there

to welcome them, ushering them into the drawing room where the Lucases and the

rest of the Fitzwilliam and extended family already sat. Elizabeth noticed with

satisfaction that her friend was already seated by the Viscount. She also noticed

something else.

"Miss Bennet?" Mr Darcy gestured at the

empty seat beside him.

"Thank you, sir." Elizabeth replied

and sat down. She noticed that he looked remarkably better than when she had last

seen him, some days ago. He appeared more robust, less frail, and much more content

with his surroundings. His wish for her company, indicated by his gesture for

her to join him, made her bold. "Your absence at Lucas Lodge, sir, was dearly

missed."

Darcy had great difficulty in withholding a gasp of surprise. Anne had been right, and he was grateful for it. It had been four days and four nights since he had first read the letter. Four days and four nights since he had decided to restore himself to his previous health. And he felt all the better for doing so.

It had been hard to realise properly for the first time how much harm he had done to himself, and the stress he had laid on his body by continuing to ignore it. The first day that he had begun was almost too much of a shock, but, by careful degrees, he had recovered enough to attire himself in the clothes that had been tailored to his more healthier form.

Now all that remain was to

court the woman he held most dear. "I am sorry for it, but it could not be

helped. My Steward had sent me a missive that commanded my immediate attention."

"I hope it was not anything bad?"

"No, thankfully it only took the night." Darcy proceeded to give her a brief but informative summary of what it had involved.

The discourse soon developed into a discussion upon the subject in general, and Darcy found himself marvelling once more at how much she knew, and on the many subjects that they were mutually interested in.

How well we are suited, he mused. Hopefully well enough to have no more

barriers before us.

"Mr Darcy, are you well?"

He

suddenly realised that he had not responded to her for quite some time. "Yes,

I am very well. Forgive me, Miss Bennet. I was just caught by the reminder of

a letter I had read several days ago. If you do not mind my asking, what was in

Anne's letter to you?"

Elizabeth blushed, as she replied. "Just

a wish that I would find happiness. Why?"

"I recently read

the letter that she wrote to me, and I found myself comforted immensely by it.

It gave me hope for something that, even in my dreams, I had never hoped to receive.

And now, I have even more cause to hope."

"Why now, sir?"

"Because I have just received confirmation from the source of my hopes,"

Darcy replied, with a significant look at her. Elizabeth gazed back.

The world faded away.

Morning seemed to give Oakham Mount particular beauty, Elizabeth found herself musing the next day, as she walked up towards the summit. The thought had been a vain attempt to distract herself from thinking about the previous evening. For thinking about it she could not avoid, as so much had happened for her to rejoice and gain hope from.

He had been

present, and all that he had always been in her company, pleasant and gentleman

like. Not once, save for the separation of the sexes after dinner, had he strayed

from her side. Nearly all of the comments he had made seemed to be meant for no

one else but her.

Did she hope too much? Elizabeth could not be sure,

hence her long walk so early in the morning, before even the rest of her family

were up. She had to distract herself, else she feared that doubt and uncertainty,

and then their two opposites would fight to reign over her mind for the rest of

the day. Even now they seemed to be winning the battle against her determination

to distract herself.

She reached the summit, gasped, and came to an

abrupt halt. Cautiously she blinked, convinced that she had imagined the sight

before her eyes.

The figure turned and spoke, confirming his reality.

"Miss Bennet," Mr Darcy uttered in greeting, "I hoped you would

be walking this way."

"You did sir?"

He came

to stand before her. "I did."

A long moment passed between

them, as he gazed into her fine eyes. Then, taking a deep breath, he made a slight

gesture to the path before them. "May I procure your company the rest of

the way?"

Elizabeth assented.

Days

passed. Now, nearly a month since he had opened that letter, Darcy stood in his

chamber, another key in his hand. Like the first, its use allowed entry into a

desk, although unlike the first, this desk was one that he always carried within.

It was a Davenport, and it contained all that he needed to sort out his estate

from a distance, and, in a secret compartment, something else.

Now he seated himself at the desk, lifted the flap, and placed the key in its hole. Gently he turned it, listening to the quiet clicks of the mechanism as it unlocked. Then he slid out the false front panel.

Before him lay a box, to which he lifted

out another key and unlocked. Bringing the box forward, he surveyed it contents.

Then he gently lifted out the smallest velvet box, opened it, checked the contents

for its condition, and, satisfied with its state, returned it to the box and slipped

it into his jacket pocket.

Carefully he restored the larger box to

its hiding place, and the desk to its previous condition. Then he rose from his

chair and walked to the window. Once more did he take out the object that lay

in the small velvet box, and surveyed it in the natural and slowly fading light.

He knew should be questioning himself as too whether it was too soon, yet, strangely,

he felt everything to be right.

It was time. He smiled and put the ring away. Gazing out at the view, he reflected over the days that had passed. Almost every moment of them he had spent in Elizabeth's company.

Without saying

a word to anyone he had begun a quiet courtship from the morning they had met

at Oakham Mount. Her enjoyment of his time with her had soon become easily detectable,

allowing his hopes to turn into certainties.

And now, or rather more accurately, tomorrow, he had arranged to meet her at the very same spot they usually met every morning, and ask her for her hand in marriage.

This was not a sudden

decision. Indeed it had been something he had planned for many days now, from

the minute he had been assured by the lady herself that she returned his regard

with the same depth of emotion as himself. She had not declared it audibly, but

it had been clearly there to see in her expression as she spoke to him.

Darcy could barely believe his good fortune. All that he hoped for now, was that she said yes.

"You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you. In declaring myself thus I am fully aware that this revelation will cause great surprise, and, amongst certain people, outright suspicion of my motives. It will also result in a complete reversal of my character."

He gently took her hands in his own. "Yet I cannot help nor deny what I feel

for you. I had never expected to feel so much, indeed to feel anything of this

nature at all. It has come upon me so suddenly, without any forewarning on the

practical bent upon which my character frequently,- perhaps now too frequently

-relies. So I beg you, most fervently, to relieve me from my suffering and consent

to be wife."

Charlotte could not refrain from gasping at such

a speech. She had never dared to hope that he would ever make such a request to

her. Or that her response would be so willing to comply with his every wish.

"My lord, I........."

"Alexis, please, my darling."

Miss Lucas blushed but managed to answer. "Alexis, I would be......

that is I......" she paused and gathered her composure. "Yes."

He seemed at first not to hear her, but then a smile came upon him, and

he turned to face her once more. If Charlotte had dared to glance at him she would

have seen how well the expression of heartfelt delight became him, but she could

only listen, as he told her how much she had come to mean to him in so short a

time.

They walked on, without knowing in what direction. There was

too much to be thought, and felt, and said, for attention to any other subjects.

Alexis offered Charlotte his arm, and they walked as closely together as propriety

allowed, while they discussed the surprise that, as each discovered, they had

both felt, in realising their feelings and developing attachment to one another.

"I was never a romantic you know," Charlotte remarked to

him, "my only desire was a comfortable home. At my age I had long given up

any hope of finding anything more. But then you arrived, and suddenly, every conviction

I had previously believed myself to hold true, was swept away, and their place

arose this."

"And it made you uncertain for the first time in your life," Alexis continued, so in tune were his feelings with her own, "I know, I felt the same thing. Society and the Ton had taught me to be forever on my guard. To expect nothing true from anyone, and to always be prepared for an ulterior motive.

"Then I met you, and all those cautions were swept away.

I realised that my practical bent, had been a result of the society to which I

had been raised with from birth. I had no expectations concerning romance, because

I never believed I would fall in love,....... until now." He turned and raised

her hand to his lips, uttering, "dearest, loveliest Charlotte."

All this and more did Miss Lucas have the honour to raise to her friend

the very next day; when she and Elizabeth were out walking, after the news had

just been made public to the neighbourhood.

"I am so happy for

you, Charlotte," Elizabeth replied, with such a smile, as to know that she

was in earnest. "And what did his family say?"

Miss Lucas

went on with her tale then, describing how, when they had returned to Netherfield,

a single glance from the Earl to his son had been all that was necessary to make

it known what had passed during their walk. Barely a minute later and the Viscount

was commanded to depart for the Lodge, to ask her father's consent.

Elizabeth

bade her friend her congratulations once more, and then returned to Longbourn,

where the cries of her mother's despair that Lady Lucas was soon to have a connection

in the peerage could be heard throughout every room of the house. Silently, she

sighed. It was not that she did not feel truly happy for her friend, it was just

that she could not help but feel envious at the same time.

She passed

the door to her father's study at that moment, and noticed to her surprise, that

the door was open. Looking up, she met his eyes, as he briefly moved them from

his book, and called to her, "ah, Lizzy, you are back. There is a gentleman

waiting for you in the parlour."

Elizabeth could not be more surprised.

Hardly daring to hope, she opened the door and stepped inside. A single look assured

her not to despair; it was he. She executed a curtsey, and verbally announced

her presence. "Mr Darcy, forgive me. Have you been waiting long?"

He had been facing the window, and seemed to instinctively know of her immediate arrival, having turned round upon the moment of her entrance, though unbeknownst to her. A silence arose as he took in the vision before him, scarcely daring to believe that the moment had come.

"No not at all," he replied softly. Leaving his habitual place of retreat, he walked back into the centre of the room, until he stood barely a step apart from her. For a moment he remained thus, gathering his faculties. Then he reached out and took her hands in his, bringing them to his lips for a lingering kiss, causing her to raise her eyes to his face; in hope and anticipation.

Quickly did he confirm both of those emotions.

"Elizabeth," he began huskily, uttering her name as one would a fervent prayer, "you must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you. How long I have felt such feelings, and how deeply they run through me, calling upon me to relieve their sufferings.

"I cannot fix upon the hour, or the spot, or the look, or the words which lay the foundation. I was in the middle before I knew that I had begun. With each passing moment spent either in or without your company, they have increased tenfold, until I could no longer delay in silence."

He withdrew one of his hands and took out the ring which had been lying in wait

in his pocket. Holding it before her, he finished his proposal. "Please will

you do me the honour of allowing me to become your husband?"

Elizabeth

could do naught else but utter her next words. "I will."

His

response was to breath a sigh of blissful relief, and then with a smile, slip

the ring on to her finger. It was thus her turn to gasp as she noticed it properly

for the first time. "This is not the same ring that........" she found

she could not utter Anne's name, for fear of making him reserved.

"No,"

he replied, understanding her half-finished query. "The Darcy Jewels contain

many engagement rings amongst them, each in their own way unique to their owner,

and I could not refrain from continuing the tradition by buying a new one to grace

your hand. Have I chosen correctly?"

"Oh yes, amethyst is

my favourite gemstone. How did you know?"

He smiled. "I obtained

the intelligence from Miss Lucas and your sister Jane." He brought the hand

to his lips, laying another kiss upon it. "Dearest, loveliest Elizabeth."

With such a compliment, she could not fail to disappoint him. "Fitzwilliam."

The next moment she was in his arms, and he was kissing her with passionate

reverence. Only when he had to break to draw breath, did he explain. "Anne

was right."

"Right about what?"

"She began her letter to me with a query about my hesitation over anyone using my full forename. As if somehow I had always imagined it to sound right when uttered by only one person. And, until now, I had never realised that truth.

"I have spent

my life searching for the one woman who could convey all she felt by one utterance.

And now I have found her." He kissed her again, his hands leaving hers to

cup her face, and then entangle themselves in her hair, until the both of them

were too breathless for either words or thoughts to pass between them.

Guiding

her to the window, they stood surveying the reflection it conveyed; of their contented

embrace, with finely matched eyes of the same depth of devotion to one another.

Darcy raised his head, letting her rest hers against him underneath his chin,

and kissed her hair in blissful contentment. "How long have I waited for

such happiness," he softly declared to her. "I love you, Elizabeth."

"I love you, Fitzwilliam."

How long they stood there neither knew, and, of those that discovered them, none dared to tell nor intrude. Mr Bennet was the first and the only, having quietly left his retreat to determine if all had gone the way he had predicted it would.

Once

he had obtained visual confirmation, he silently withdrew, and returned to his

sanctum in order to contemplate the happiness he felt for his favourite, and the

depth of the loss he would have to bear when she parted for Pemberley.

Afternoon had faded into evening long before the suitor parted from his fiancee to seek consent from her father. He emerged from the room half an hour later, with an agreement and a invitation to dinner, which he happily accepted.

Returning to

her side, he remained thus in silent contemplation the rest of the night, while

the declaration of their future union was left unannounced until the morrow.

"Did you know how I felt?" He could not help asking when she

saw him to his carriage in the darkness of the night.

"Know, no.

Hoped, wished that you did, yes." Elizabeth smiled at him, as he silently

listened to her reply, marvelling over how the starlight seemed to be mirrored

in her fine eyes. "Anne's letter had given me her view, but I could not be

certain. Even if I had truly heard those words."

"What words?"

"When I stayed behind at Hunsford with a headache, and you came over.

You caught me as I fainted, and I thought I heard you utter what you began your

proposal with."

"I did," he replied, amazed and pleased

that she had indeed heard the words he had never intended her to hear then, having

not the courage nor the position to utter them. "Did you also," he asked

softly, "feel this?" He repeated the kiss he had given her that night.

"I did," she answered with a blush, "but I never realised

until now."

He came to a halt outside his carriage, turning to

face her. "Goodnight, Elizabeth." He kissed her again.

"Goodnight Fitzwilliam." Parting is such sweet sorrow, that I shall say goodnight till it be morrow.

"A report of the most alarming nature

reached me two days ago. Though I know it to be a scandalous falsehood, though

I would injure her memory so much as to suppose the truth of it possible, I instantly

resolved on setting off for this place, so that I might make my sentiments known to

you. And to have the report universally contradicted."

Darcy looked

at his Aunt sadly. "I am sorry, Lady Catherine, but to have the report universally

contradicted is impossible. I am engaged to Miss Elizabeth Bennet, and we will

marry as soon as every thing required can be sorted."

"This

is not to be borne! Nephew, I insist on being satisfied! Have you lost all sense

of reason?"

"No, in fact, Aunt, I do not believe I have never been more sensible in my life." Darcy stood up from his chair and leant against the desk.

To the casual observer, this may have looked like a relaxed posture,

but to those that knew Fitzwilliam Darcy well, it was one of barely restrained

anger. "You can have no reason to object to what is my own life. You have

had no claim on it whatsoever."

"Have I not? Was it myself

who planned, while you were in your cradles, to marry you to my daughter?"

"Yes,

but the arrangement was never a formal one, only a wish of yourself. The only

reason I entered into the match in the first place was because I had Anne's agreement

that it was solely for the sake of Georgiana and Anne herself. Why, now that I

am unattached once more, should I hold myself back from marrying again?"

"Because honour, decorum, prudence,- nay interest, forbid it!" Lady Catherine replied, her voice rising once again beyond the levels of normal. She paced for a while in front of him and the desk that he leant upon, in proud, forceful strides.

Suddenly she stopped and turned to him again. "I see your

design! And now, perhaps, I am not quite so displeased. The continuation of your

family's line is of course a priority, I quite understand. But surely you could

have made a better choice, from among those of your own circle."

"Lady

Catherine, to suggest that my marriage to Elizabeth is due to no other desire

than to procure an heir, is an insult to both her and myself. I have asked her

to be my wife out of no other interest than everlasting love, and she has replied

to me with the same."

"You may believe that nephew, if you

choose, but her arts and allurements have only lead you to believe this. She has

drawn you in."

"Quite the contrary, Aunt. It is a result

of mutual attraction on both sides."

"Oh this is not to be

endured! The upstart pretensions of a young woman without family, connection,

or fortune. If you were still possessed by sense, you would not wish to lower

yourself out of the sphere in which you have been brought up."

"In

marrying Elizabeth, I should not consider myself as quitting that sphere. I gentleman,

she is a gentleman's daughter: so far we are equal."

"But

who is her mother? Who are her Uncles and Aunts? Do not imagine me ignorant

of their condition."

"Elizabeth's connections do not matter

to me," Darcy replied, by now almost beyond his limit, "thus they can

mean nothing to you."

"Unfeeling, selfish, nephew! You refuse

to oblige me? You refuse to obey the claims of duty, honour and gratitude. You

are determined to ruin yourself."

"The only thing I am determined

in, Aunt, is to act in a manner which will constitute my own happiness without reference to you, or to anyone so wholly connected to me."

"And this is your final resolve? Very well, I shall know how to act.

You are aware that if you follow this course of action I shall endeavour to do

everything in my power to ensure that you do not inherit Rosings upon my death?"

"I do not care whether or not I get Rosings!" Darcy snapped,

finally losing his control.

"You do not care it seems about a